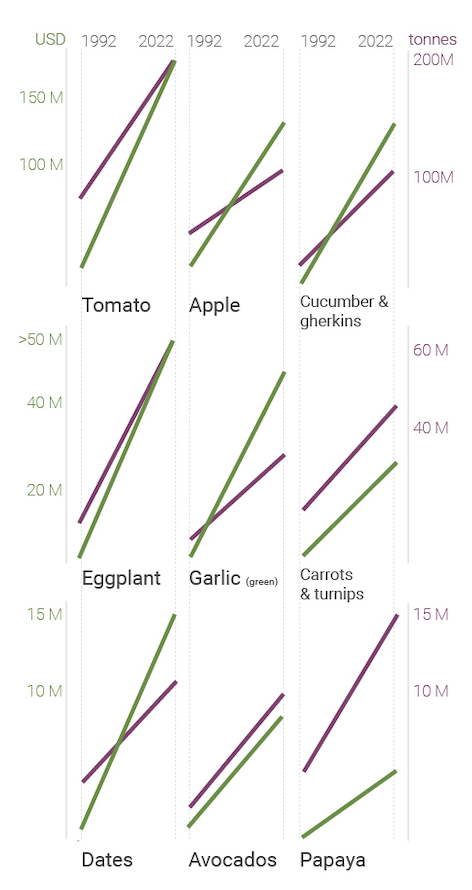

It is perhaps not surprising that any crop grown is not just food or material, but also a value based commodity. As such, the choice of crops to be grown for an individual or a nation is a social, political and economic decision. Curious about shifts in agriculture practices across the globe, I analysed economic valuation of crops across three decades. It became clear that a lot fresh produce vegetables and fruits have seen higher change in their valuation, with production treading along (Figure 1). Tomatoes, apples and cucumbers & gherkins have the highest valuation among fresh produce items, globally. This may be indicative of growing population, higher demand for fresh foods and nutrition, a shift towards vegan/vegetarian diets, and higher demands for exotic produce.

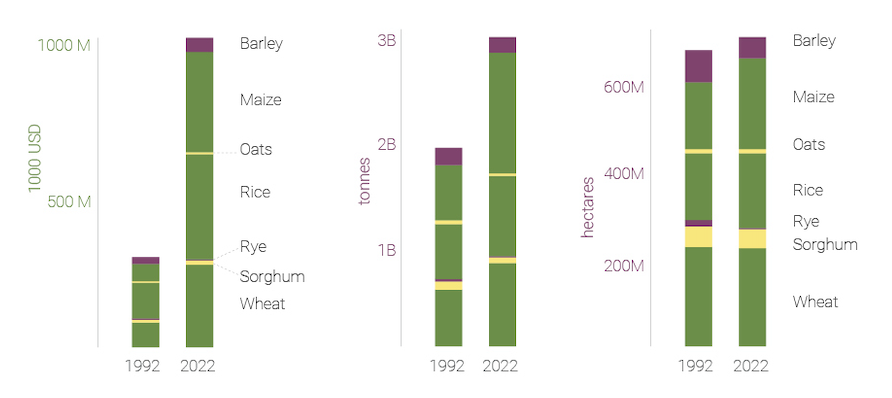

It is to be noted that the staple cereal crops still have a higher valuation and much higher production, but the change in valuation of fresh produce if of interest (Figure 2).

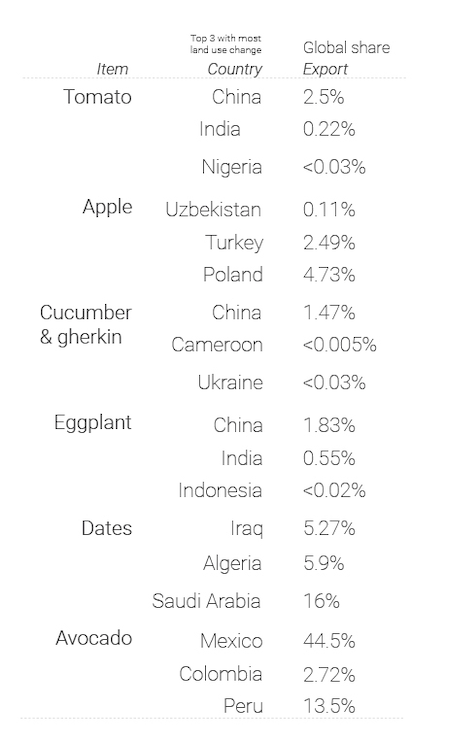

Next, I looked for countries that had started to dedicate more land to these high-value fresh produce crops (Table 1).

Curious if the crops were grown for local consumption or exports, I looked up each country’s export share for these produce items (Table 1). It revealed that many fresh produce like cucumber, tomatoes, and eggplants are grown for local consumption.

China and India are the most populated countries in the world and consequently have higher requirements for all food items. While more exotic items like avocados, dates, and apples are made for export. It reiterated the importance of choice that a nation has to make about consumption and trade regarding crops it chooses to farm.

Since all these items are land-based crops, with their production increasing, one would expect that land harvested for these crops would rise as was seen in the analysis (Figure 3).

One would expect that most countries have also increased land used for agriculture. However, amongst the countries analyzed only China (and India, data not shown) have shown a substantiative increase in agricultural land (Figure 3). Iraq has a huge shift in land dedicated to agriculture, with an acute dip concurrent with the American invasion of Iraq (data not shown).

Interestingly, data shows that some countries have reduced the area dedicated to certain cereal crops. Mexico, for example, has reduced the area used for wheat crops, and Algeria and Iraq have done the same for barley crops. China, while has increased the area for corn harvest, has decreased so for wheat harvest. Uzbekistan, on the other hand, has increased land used for wheat cultivation, with a decrease in land used for barley and cotton, another economic crop.

I also inquired if these countries that use less land for cereal crops are able to fulfill local needs or rely on imports. China, actually, is the largest importer of cereals in the world, followed by Mexico. Algeria and Turkey rely heavily on cereal imports to meet their local needs (Table 2).

While this analysis doesn’t bring me closer to understanding how each country decides what crops to grow, it highlights that it is indeed a strategic decision. If a country foresees potential in export opportunity for a crop with high valuation, it may do so at ‘expense’ of other crops that are locally needed. Understanding agricultural trade dynamics across globe might be revelatory of barters and exploits between producers and consumers.

Data sources:

FAO datasets

1. Value of agricultural production

2. Crops and Livestock Products

https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QV/metadata

Retrieved in September 2024

OEC reports

https://oec.world/en/profile/hs/cereals#exporters-importers

Retrieved in December 2024

All the datasets were first analyzed using Tableau and then recreated in Illustrator.