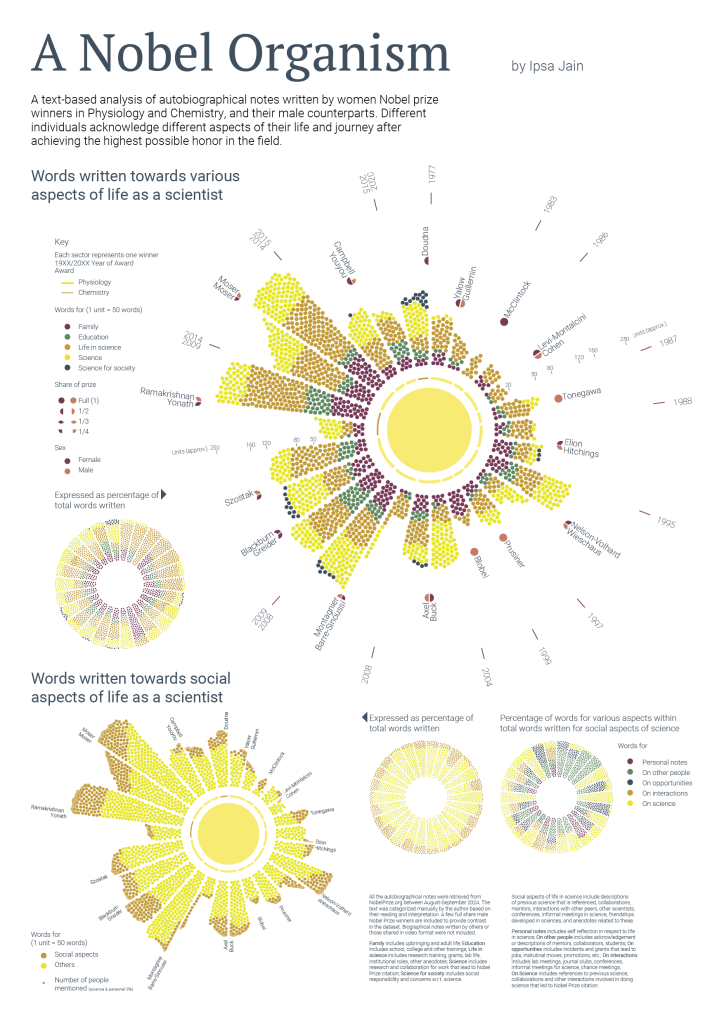

Biographies of scientists are important as they allow a window into science as a way of life and the cultures of science. They also highlight/hint at socio-political-cultural complexes within scientific institutions. They betray the values of a scientist, scientific, social, and personal.

Nobel Prize winners, the highest achievement in sciences, deliver Nobel prize speeches and are also directed to write autobiographical notes for the Nobel Prize website. These autobiographical notes are a reflective piece where the scientist charts their journey from the beginning, sharing how events and people have shaped their scientific journey and work. They mention upbringing, education, training in science, institutional associations and roles, movements across institutes, meetings with people, references that influenced the work, interactions with mentors, friends and collaborators, students, love life, engagement with arts and more. Different scientists bring up different aspects to their journey, from joy of friendship to grief of war to loneliness of being a head strong scientist in their time. It was remarkable that a lot of the winners, (in some cases, even with apparent grandiosity) acknowledged how other people have contributed to the life and work that led to the Nobel Prize award. As Newton said, “if I have seen further [than others], it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” If the giants could include not only previous thinkers, but all the people in scientific ecosystem from mentors to students to technicians that contributed to the work! Awards like Noble Prize may glorify the idea of a lone scientific genius but a study of these autobiographical notes is a reminder that it is anything but that.

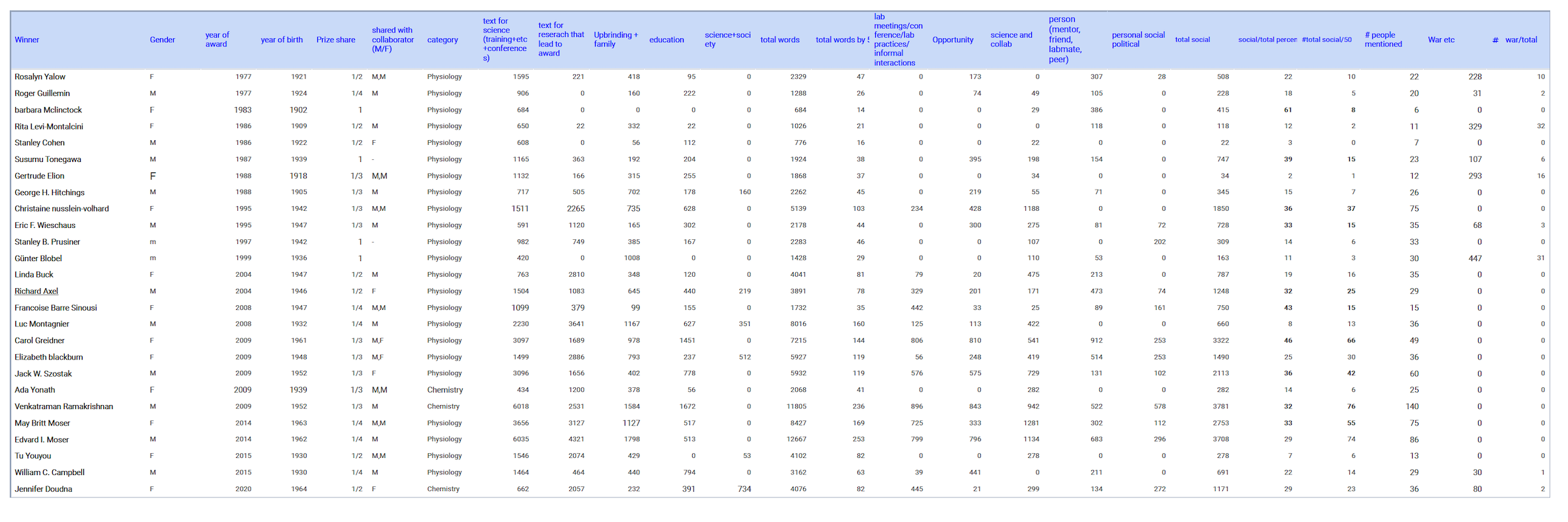

In this project, I started out to analyse the humility, acknowledgement of others in the writing of each women Nobel Prize winner and their male counterparts. I theorised that perhaps women are more grateful than men. The markers I used were, mention of names in the notes, mention of social interactions, words to praise/express gratitude towards specific people, words written towards lab cultures like meetings and conferences that are social in nature, on situations where others open doors/created opportunities for them. Using these markers there were no obvious gendered differences in dataset I worked with. Perhaps other methods like discourse analysis or larger dataset might make these clarified.

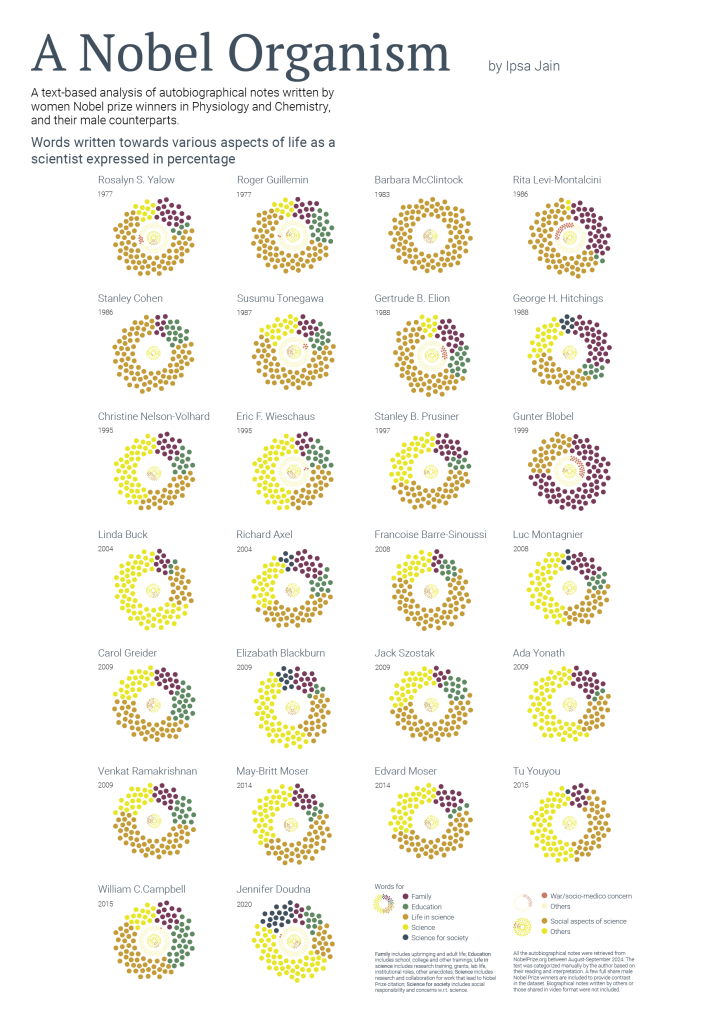

Method: I read each biographical note 2-3 times. I placed sections of text under each subheading as outlined in analysis in an excel sheet and counted number of words. Simple arithmetic was used to scale down number of words by a factor of 50. Words for social aspects and war were similarly extracted from the notes and counted.

My favourite reads included Carol Grieder, Christian Nelson-Volhard, Richard Axel and Gunther Blobel.

Some things that I noted but didn’t come up in the visuals:

Eric Kandel has influenced many a scientists directly and indirectly.

DNA structure discovery and people associated were also mentioned often.

Women scientists mentioned Rosalind Franklin or Barbara McClintock as inspirational figures.

Most of the winners had shifted institutions/cities within their research journeys.

Most of the winners had good relationship with their research mentors (and few even shared awards with them).

Some winners that didn’t speak much towards social aspects of science were research centric in their notes.

A few women winners mentioned how their life partners have influenced their decisions and research journeys. Fewer men mentioned the same.

My fav story from all the notes is this one by Carol Greider:

“The friends in Stanley Hall were a very close group. We would walk to get a latte at least once every day. We would talk science, tell jokes, tease each other and complain to each other about experiments that did not work. There were a lot of practical jokes that we played on each other. I was having trouble with experiments one afternoon and complained to Jeff that I was “bored”. So late that night Jeff filled my umbrella with home made confetti with the word bored on each piece. The next day I was leaving genetics class, it was raining so I opened my umbrella and thousands of pieces of paper fell out. I knew I had to retaliate. The next day I got into the lab very early. I went to Jeff’s lab bench; he had 40 bottles of different chemical reagents for his experiments lined up on the shelf above his bench. They were all glass bottles filled with clear liquid, I removed the labels that were taped on for every one of them (I marked each with a number underneath and kept a paper key). When Jeff came in to work in the morning, he started his experiment for the day, reached up for his TE buffer and found 40 identical unlabeled bottles. He was shocked at first, then, being clever, he saw the small numbers on the bottom and realized what I had done. He came into our lab and said “OK so where is the key?” I pretended to not know what he was talking about, but was glad when he admitted I had gotten him back. These kinds of jokes were common in Stanley Hall. Often they involved dry ice inside plastic tubes, which would burst and sounds like a bomb when placed in a metal garbage can.”

Reading and plotting these notes has been source of joy. A peek in the life of science in a way that I can relate to as well as the one I shall not experience.